https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-11/the-dangerous-rise-of-the-supersized-pickup-truck

What Happened to Pickup Trucks?

As U.S. drivers buy more full-size and heavy-duty pickups, these vehicles have transformed from no-frills workhorses into angry giants. And pedestrians are paying the price.

To get a handle on what's happened to pickup trucks, it really helps to use a human body for scale.

In some nerdy Internet circles — specifically, bike and pedestrian advocacy — it has become trendy to take a selfie in front of the bumper of random neighborhood Silverados. Among the increasingly popular heavy-duty models, the height of the truck's front end may reach a grown man's shoulders or neck. When you involve children in this exercise it starts to become really disturbing. My four-year-old son, for example, barely cleared the bumper on a lifted F-250 we came across in a parking lot last summer.

Look out below.

Photo courtesy Angie Schmitt

Vehicles of this scale saddle their drivers with huge front and rear blind zones that make them perilous to operate in crowded areas. Even car guys have been sounding the alarm about the mega-truck trend recently. A few months ago, the Wall Street Journal's Dan Neil complained about his close encounter in a parking lot with a 2020 GMC Sierra HD Denali: "The domed hood was at forehead level. The paramedics would have had to extract me from the grille with a spray hose."

Since 1990, U.S. pickup trucks have added almost 1,300 pounds on average. Some of the biggest vehicles on the market now weigh almost 7,000 pounds — or about three Honda Civics. These vehicles have a voracious appetite for space, one that's increasingly irreconcilable with the way cities (and garages, and parking lots) are built.

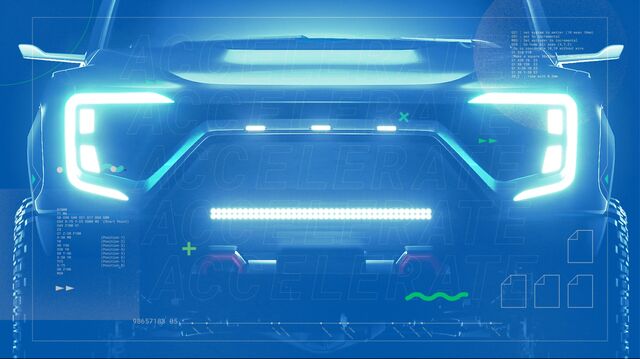

Styling trends are almost as alarming. Pickup truck front ends have warped into scowling brick walls, billboards for outwardly directed hostility. "The goal of modern truck grilles," wrote Jalopnik's Jason Torchinsky in 2018, "seems to be… about creating a massive, brutal face of rage and intimidation."

The Electric Pickup Truck War Is Here

During the pandemic, U.S. buyers seemed to respond to this kind of packaging. In May 2020, Americans bought more pickup trucks than cars for the first time. Five of the 10 top-selling vehicles in the U.S. last year were pickup trucks.

Giant, furious trucks are more than just a polarizing consumer choice: Large pickups and SUVs are notably more lethal to other road users, and their conquest of U.S. roads has been accompanied by a spike in fatalities among pedestrians and bicyclists. As I wrote in my 2020 book Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and the Detroit Free Press have pointed to the rise in SUVs and large pickups as the main culprit in the pedestrian mortality surge.

The truck trend is contributing to another troubling crash-related disparity: In a new study, the IIHS shows that women — who tend choose smaller vehicles — are suffering higher injury and death rates than their male counterparts, despite the fact than women engage in fewer risks and crash less.

Why have pickup trucks morphed into such huge, angry, and dangerous presences? Traffic safety experts, commentators on U.S. automotive culture, and social scientists have suggested a range of forces behind truck bloat.

The truckification of the family car

One key driver of pickup growth relates to how they are now being used. If you overlook their gleefully violent styling and garage-unfriendly footprint, these vehicles have become more practical as family vehicles.

Despite the agrarian pursuits that TV commercials suggest, today's pickup trucks are being built more to haul kids and families than sheep and boulders. Until the 1980s, almost every pickup truck sold in the U.S. had a single cab, meaning seating for three max in a single bench-style seat, with a bed that was eight feet long for a full-sized long-bed vehicle. That old no-frills working-style truck is fading into history.

In 1967, this was a pickup truck.

Photographer: Underwood Archives/Archive Photos

In 2020, 85% of pickup trucks sold had "crew cabs" or "extended crew cabs" or one of a handful of other tough-guy euphemisms with two sets of seats for five people — most with four doors. Some have four regular-size doors. These passenger-heavy, cargo-lite arrangements are so popular that some automakers — like Ram — have stopped even offering single cabs in their best-selling pickup brands.

As pickups transformed into family vehicles, they also became more luxurious. The average truck in the U.S. sells for almost $50,000 now — a 41% increase compared to a decade ago — and many boast posh, feature-laden interiors designed to compete with high-end SUVs and sedans, as auto writer Jim Gorzelany writes in Forbes.

As a result, today's truck owners include all kinds of people who don't necessarily need (and rarely use) these vehicles' defining features: the open cargo-hauling bed and towing capabilities. Some choose big trucks because smaller vehicles make them feel too vulnerable on modern highways.

Michael Powell, a social worker who lives in rural Maine, says he'd rather drive a compact car, but he has PTSD from a former car crash: He drives a truck, he says, "because everyone else in my town does, and it's the only way I can get around without feeling like I'm gonna die."

Jeff Weidner, an assistant professor at a college in El Paso, Texas, says he feels a little guilty about choosing to buy a full-size Toyota Tundra — but admits he likes it. "We were looking for something that would hold six people, would be good for long trips in terms of space and carrying our stuff," he says. At first, he planned on buying the mid-size Tacoma, but "they upsold us hard with the Tundra. They barely even had stock of Tacomas — they probably do not make enough money on them."

The U.S.'s perverse regulatory and tax environment contributes to this arms race. Ford's heavy-duty F-250, for example, benefits from its regulatory status as a commercial vehicle, unlike the slightly smaller F-150. The same goes for other heavy-duty models like the Ram 2500 and Silverado 2500HD, which aren't classified as passenger vehicles, but as work machines, and are thus exempt from EPA fuel economy reporting regulations. "Nobody tracks the gas mileage — there's no EPA rating for that car," says Dan Albert, author of Are We There Yet?: The American Automobile Past, Present and Driverless.

The mighty prow of a GMC Sierra Denali HD.

Photographer: Sandy Huffaker/Bloomberg

Business tax structure also encourages many business owners to opt for the bigger F-250 over the F-150, making the added cost almost negligible. Going large doesn't necessarily exact a major toll in fuel expenses, either: While pickups have gotten bigger they have also become — while not exactly green — certainly less gas guzzling. Equipped with a hybrid powertrain, the 2021 Ford F-150 can achieve 25 miles per gallon in the city, six more than a Honda Odyssey minivan. "We have gotten better at making them more efficient," says Benjamin Sovacool, a researcher who studies energy transitions.

That fuel efficiency is set to leap forward again, with the arrival of Tesla's Cybertruck, GM's rebooted 1,000-horsepower Hummer EV, and host of other electrified rigs: battery-powered vehicles that overcompensate for their non-polluting powertrains with hyper-aggressive styling and power ratings.

Make way for "petro-masculinity"

But that doesn't mean the decision to buy a $50,000 truck with a 4,200-pound payload rating for the occasional trip to the golf course or hardware store is strictly rational. Personal vehicles are not merely functional appliances: They are used as refuges, fortresses and private enclaves, and serve as important signifiers of class and gender identity, as Sovacool explored in a 2018 study.

To Albert, the booming appeal of bigger and more brutish trucks reflects "a crisis of masculinity," he says. "Nothing could be more emasculating than driving a minivan. So you want the vehicle that's going to maintain your performative masculinity."

The fact that supersized pickup trucks were often deployed as political props (and weapons) during the Trump era did not escape the notice of scholars like Cara Daggett, a professor of political science at Virginia Tech. In a widely shared 2018 journal article, Daggett coined the term "petro-masculinity" to describe flamboyant expressions of fossil fuel use by men (and some women as well, but mostly men) as a reaction against social progress. To these drivers, "the affront of global warming or environmental regulations appear as insurgents on par with the dangers posed by feminists and queer movements seeking to leach energy and power from the state/traditional family," she wrote.

Petro-masculinity helps explain not only these vehicles' confrontational styling, but the often equally belligerent way in which they are operated.

The EPA estimates that more than half a million trucks — 15% of the diesel-powered pickups on U.S. roads — have had their emissions equipment modified over the last decade in order to increase their power and polluting potential. There's a cottage industry devoted to the practice of bypassing emissions standards; such modified vehicles are believed to emit as much pollution as 9 million emissions-compliant diesel trucks. While illegal, some drivers flaunt their ability to pollute, via the behavior known as "rolling coal," in which drivers of modified diesel trucks blow black smoke at targets of their disapproval (often Prius drivers or bicyclists).

"Burning fossil fuels can come to function as a knowingly violent experience," Daggett writes, "a reassertion of white masculine power on an unruly planet that is perceived to be increasingly in need of violent, authoritarian order."

Built for battle

Geopolitical factors have long played a role in car and truck design in the U.S.: Jeeps, of course, began as military vehicles adapted to civilian use, a heritage the company still proudly announces on its site, saying the brand is "forever tied to freedom, capability and adventure." The first iteration of GM's Hummer brand spun from the high-profile role that Humvee military vehicles used in the Persian Gulf War. Other manufacturers continue to cultivate connections to the military as well. Ford advertises its F-150 is made of "military-grade aluminum alloy" for the "working warrior."

In his excellent illustrated essay "About Face," cartoonist Nate Powell, whose father was an Air Force officer, explores the recent emergence of the overtly "paramilitary aesthetic" in truck and SUV design and connects it to recent U.S. "forever wars," in which regular troops have mixed with private security units, special forces and law enforcement officers in battlefields around the world. Many veterans of these campaigns employed up-armored civilian vehicles, and they brought a taste for such machines back home with them.

That aesthetic can be detected not only in the raised "militarized" grille height of pickup trucks, but also the popularity of aftermarket modifications like blacked-out windows and "bull bars" affixed to the front end. Together, the way these trucks look speaks to a "rejection of communication, reciprocity and legal accountability," Powell writes.

At their heart, these consumer choices also reflect something else, says Sovacool: fear. "We are questioning our place in the world, with globalization and Trump. We're also feeling really uncertain and unsafe — the pandemic, terrorism."

With its "bulletproof" stainless-steel skin and "bioweapon defense mode," perhaps no vehicle feels as precisely calibrated to the anxieties of its era as the Tesla Cybertruck. Such vehicles promise more than just "defensive security," wherein a larger vehicle at least theoretically protects its occupants better in a collision with a smaller vehicle: They are built to project "offensive security," Sovacool says.

"If you do need a vehicle that will go off road, carry lots of weapons or run over people," he says, "then these bigger vehicles do it better than these smaller ones."

Only in America

Threaded within the pickup's militaristic branding is a powerful appeal to national pride. U.S. automakers have long dominated pickup truck sales, which produce enormous profits for Detroit-based companies and employ a lot of domestic auto workers. No wonder there's such hesitancy among regulators to stand in the way of some of their more egregious styling trends or emissions loopholes. "In a way, critiquing them is seen as anti-American and anti-jobs," says Sovacool.

America's "Big Three" automakers dominate the large pickup market.

Photographer: Jack Smith/Bloomberg

In a 2016 essay for N+1, Albert also reflected on the burden of associations — nostalgic and nationalistic — that pickups carry: "To drive a thirsty truck is to live in a pre-EPA era, before the spikes in gas prices, before political correctness," he wrote. "To fill the bottomless tank of a pickup … is to practice the religion of the American Way. It is to affirm climate denial, petrol-adventurism, and American exceptionalism."

There are many ways to untangle pickup trucks from this trap and rein in their most destructive excesses. Federal regulators could revise the EPA mandates that the largest pickups now avoid, and impose stronger rules on pedestrian safety to make trucks and SUVs less lethal. The tax code could be reformed, so businesses that purchase the largest commercial trucks aren't rewarded with a 100% depreciation bonus on the first year. Cities could stiffen parking policies and raise vehicle fees so that such impractically scaled machines will be less appealing to buyers who have little need of their capabilities. But any such efforts can't be merely "technocratic," Daggett says — they must grapple with the broader societal forces that these supertrucks have tapped into.

"A lot of things are attached to fossil fuel culture because they are symbolically a part of a certain way of life or an identity," she says. "It's no longer possible to operate in the world and not understand that fossil fuels are violent. It's a kind of spectacular performance of power."

Angie Schmitt is a writer and planning consultant and author of Right of Way: Race, Class and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America.

Jason @BeardedOverland www.beardedadv.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment